The main output of the define phase within the DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control) methodology is the project charter. Without having a completed project charter in place, the measure phase makes little sense.

As much as the DMAIC methodology gives us our project path, the project charter is responsible for where the path leads us to.

To address this question, let’s look at what should be on the project charter. There are a few information basics that all project charters should have.

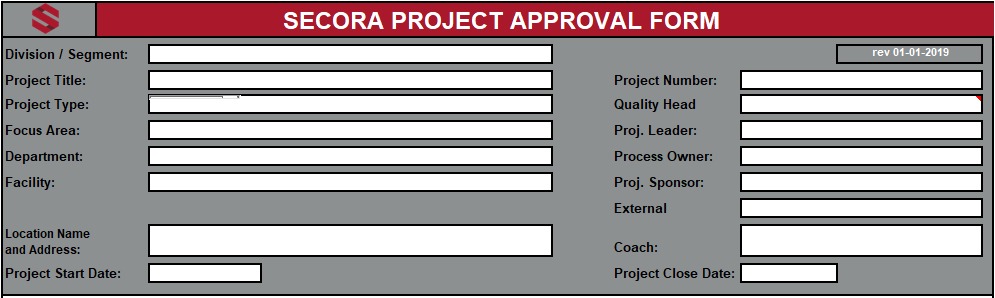

The top part of your working charter should include “where” the project is being done, “who’s” doing it, “when” it’s to be done, and support persons in the project like finance, sponsor, coach(s) and process owners. This initial information will give the viewer an immediate snapshot of your project’s basics.

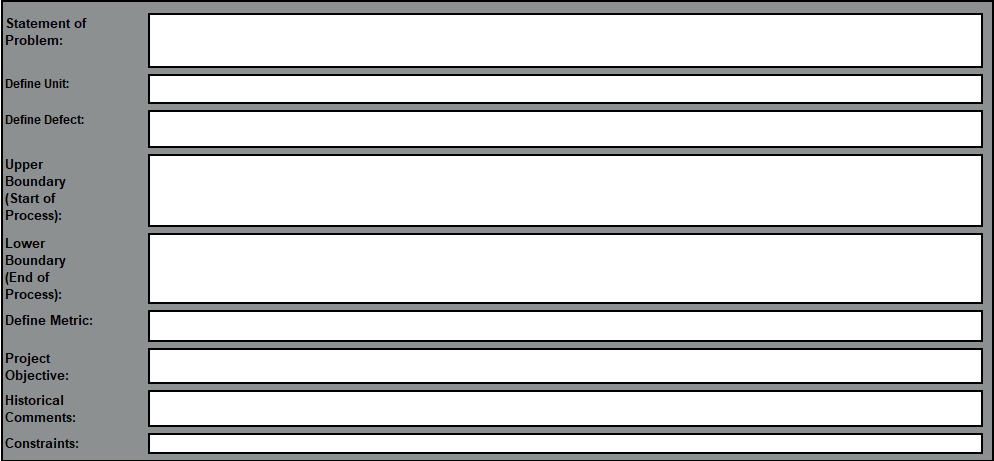

Next is the detailed explanation of your actual project and the issue that needs optimization.

The problem statement should describe the business pain in a clear, easy to understand, manner, and as short as possible. Remember, you’re describing a pain: just as if you were sent to the emergency room, you would tell the doctor exactly where it hurts, how it hurts, and how long it’s been hurting.

The unit is what you’re measuring. Examples would be boxes, bumpers, forms, deliveries, or changeovers.

The defect is what is wrong with the unit. Examples of defect (using the above examples) would be empty (boxes), scratched (bumpers), incomplete (forms), late (deliveries), and long (changeovers).

Upper boundary (start of the process) is a description of where the business pain starts. The easiest way to see what goes in there is to align it with the first process step in your SIPOC (suppliers, inputs, process, outputs, and customers). Make sure there’s a verb in this box. You should be describing a function, a task, or an action. Keep it short and simple. Examples would be form arrives, line stops, customer calls, or material added.

Lower boundary (end of the process) is a description of the last process step in your SIPOC where the business pain takes place. Make sure there’s a verb in this box. You should be describing a function, a task, or an action. Keep it short and simple. Examples would be form completed, line starts, customer call made, or material -used up.

Metric is a combination of unit and defect. This box also allows you to identify other metrics you plan on measuring that have nothing to do with the actual problem statement. For instance, your primary metric could be number of empty boxes (empty=defect, boxes=unit) and your secondary metric line speed, where you seek to reduce the number of empty boxes, but keep line speed the same. Or, your primary metric could be changeover time and your secondary metric number of changeovers per day.

Project objective is a clear, easy to understand, and short as possible description of what you want to achieve with your project. You need to incorporate your metric into this description. As with the upper and lower box, a verb has to be in the objective. Examples might be: Reduce changeover time from 20 minutes to 10 or increase number of calls answered from 40 to 60 per hour. Alternatively, you can also incorporate your secondary (or multiple metrics) into your project objective such as: Decrease number of empty boxes from 200 per batch to less than 50 while keeping line speed at 3 000 boxes per hour.

Historical comments are where you can direct attention to previous attempts to solve this problem. It may include past projects, changes in the process, or anything that was done within your process scope.

Constraints are either out of scope issues or barriers that may hinder the success of your project such as vacation time (Christmas holidays), a new process owner on the job, or any other technical or staff-related hurdles your sponsor should be aware of.

The final installment of your charter gives weight and importance to your project. For this reason, you should spend time here getting it right.

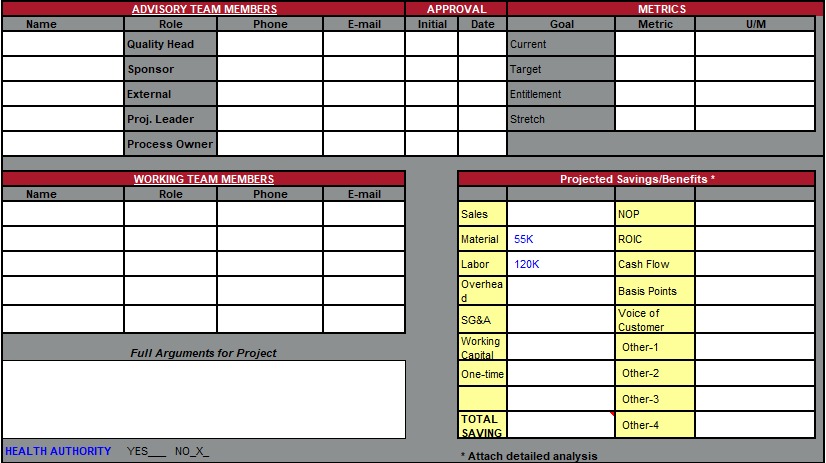

Advisory team members are those people who have a vested interest in the success of the project. This includes (but is not limited to) the supervisor such as the general manager, site director, or department head. Furthermore, the actual sponsor of the project, who should be able to remove any barriers (financial or personnel) to the success of your project and has final say on all approvals (gate reviews) within your project, needs to be named here. Often, this can be the same person mentioned in the supervisor box. The financial person is the one who calculates and verifies the financial impact of your project and in most cases, will be a controller or financial manager. Your name, together with that of the process owner, who is directly responsible in tandem with you for the success of the project, should go into the Belt box..

Approval is essential to this project charter. Here advisory team members commit themselves to their functions within the project. This should be seen as a contract with responsibilities and consequences.

Metrics are the set of targets those identified in the advisory team member area commit themselves to reaching. Here you have your current status (200 empty boxes), target (50 empty boxes), entitlement (60 empty boxes), and stretch (30 empty boxes)—otherwise known as the specification limits for your project. [Upper specification level (60 empty boxes), target (50 empty boxes), USL (30 empty boxes)].

Working team members are those people whom you and the process owner have selected to assist you in finding the root cause for the business pain. These people should have intimate knowledge of the process and be directly involved within it.

Projected financial savings/benefits are to be filled out by the financial person mentioned in the advisory team member area. You may have various areas where your project will have a financial impact. The more your finance person knows about the project, the more exact he/she can estimate its financial impact.

Business case is where you motivate arguments for your project and why it should be prioritized. Outline all non-financial reasons why this project is important and should be done, and what positive impact it’ll have (on the business or individuals). Write the business case compellingly and in such a fashion people would want to fight to get on your project team. Keep the project charter short and simple, but feel free to make your point. The more convincing you make your business case sound, the higher probability you’ll get the necessary resources, time, and priority to your project.

To find out how SECORA can further help you improve processes, reduce waste, and increase market share, check out our offering at SECORA.